Last week I submitted my PhD thesis corrections. After six years of study, drawing, making and writing, I can say that I have completed my research project; I would like to share my research findings in this blog post.

The outcome is a design framework for the creation of illustration shown below:

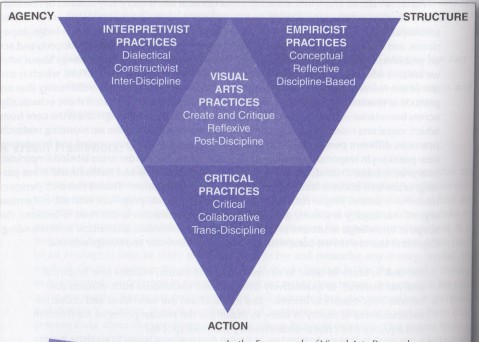

This framework is based on the ‘braid’ metaphor proposed by artist and theorist Graeme Sullivan. I used the research structure designed by Sullivan to describe how my project followed a systematic and rigorous research process. This enabled me to frame my creative enquiry as academic research and argue that my conclusions are valid contributions to knowledge in line with PhD requirements.

The design framework I elucidated enabled me to view both theoretical and practical research processes as aspects of a single, whole project. The project made use of multiple research ‘strands;’ these were: empirical, critical, interpretive, and visual art practices.

The subject of my research is picturebook illustration as a platform for intercultural communication between readers. Therefore, I mapped my research contexts and practices onto the four strands of Sullivan’s braid framework, which I will now describe.

The empirical aspect involved observational drawing, taking photographs, and collecting ephemera from my environment. These collected visual data informed and constructed my illustration work. Critical aspects of my work involved reading theories applied to children’s literature that have evidenced cultural and ethnic oppression in books for children. These include: Postcolonialism, Critical Race Theory (CRT) and Orientalism; therefore, my work investigated how these issues can be addressed in picturebook illustration in the context of a culturally diverse society. Interpretivist aspects of my work involved viewing empirical visual data through the lens of the critical analyses of picturebooks. This stage involved experimenting with visual content and illustration technique. I explored what the picturebook may signify as an artefact rooted in western culture and what tensions, juxtapositions and potentialities exist in the meeting of global and local aspects of visual storytelling in picturebooks created in the UK. The visual arts element of my research merged all of the previous aspects of my illustration research to draw conclusions and make design decisions on how picturebook illustration would be approached theoretically and practically. I found that images encode information that provide clues to the structure of stories, and that stories are constructed with narratives: such narrative structures are used in storytelling internationally. By relating narrative theory to visual narrative, I concluded that visual narrative provides readers with a space for the imagination to co-construct the narrative based on one’s own experiences and cultural references. Individual interpretations can then be shared and discussed with fellow readers resulting in intercultural communication when read in culturally diverse groups. Visual art in the context of my research project, therefore, explored narrative structure, reduced cultural identifiers and the format and design of the picturebook as a way to provide more space for interaction and interpretation of the story by readers. Some of my practical outcomes are shown below:

Through three phases of practical research, I found that the process of making illustration is in itself a culturally diverse and complexly constructed activity when made in globalised and culturally diverse societies. I found that it is unproductive to disentangle individual cultural identities from one another when multiple cultural references are enmeshed in the work of an illustrator through their research processes. This idea is, however, limited in the context of interculturalism which requires equality between cultures in order to be described as ‘intercultural’. As the children’s book publishing industry in the UK remains a culturally biased one, picturebooks cannot be described as ‘intercultural’. However, the dialogue arising between readers as part of the picturebook reading process, in a culturally diverse readers, can be said to be ‘intercultural communication’. In final, third stage of my research, therefore, I sought to find how illustration enables this intercultural communication, as well as how picturebook illustration supports and can further encourage such communication when making artwork for picturebooks.

Importantly, picturebooks tell stories through image as well as verbal language, which allow readers who do not have English as their native language to engage more readily with the narrative. By readers being able to engage with the narrative, cultural and linguistic abilities and knowledge are not such a restriction. With images to support reading and discussion, readers of all linguistic and cultural backgrounds together can be encouraged to create a safe space for pupils to voice their interpretations and opinions (2014b). By reading picturebooks, windows, mirrors and doors are formed which allow insight into lives of other people and cultures, as well as the opportunity to reflect on one’s own. “The mirror invites self-contemplation and affirmation of identity. The window permits a view of other people’s lives. The door invites interaction” (Botelho & Rudman 2009 p.xiii). Illustration and design of picturebook narratives thus encourages critical cultural awareness and enables intercultural communication between readers (Arizpe et al. 2014b).

To summarise, I found that visual storytelling contains both global and local elements, which, along with the cultural identities that readers bring to the narrative, form a platform for intercultural communication (Propp 1968; Quental 2014; Arizpe et al. 2014b; Lloyd 2014).

Some of this text was taken from my thesis and adapted for this blog post.

References:

Arizpe, E. et al. (2014b) Visual Journeys Through Wordless Narratives: An International Inquiry With Immigrant Children and The Arrival, London: Bloomsbury Academic

Botelho, M.J. & Rudman, M.K. (2009) Critical Multicultural Analysis of Children’s Literature: Mirrors, Windows and Doors London: Routledge

Farrell, M. et al. (2010) Journeys across visual borders: Annotated spreads of The Arrival by Shaun Tan as a method for understanding pupils’ creation of meaning through visual images Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, The, 33(3) p.198

Lloyd, P. (2014) The high street as a portrait of the artist: An interview with Jonny Hannah Journal of Illustration, 1(2), pp.301–319

Propp, V.I. (1968) Morphology of the folktale 2nd Ed. Austin: University of Texas Press

Quental, J. (2014) Searching for a common identity: The folklore interpreted through illustration Journal of Illustration, 1(1) pp.9–27

Sullivan, G. (2010) Art Practice as Research: inquiry in visual arts 2nd Ed. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE